5 Ways Learning Braille Can be Fun and Games (with Annie!)

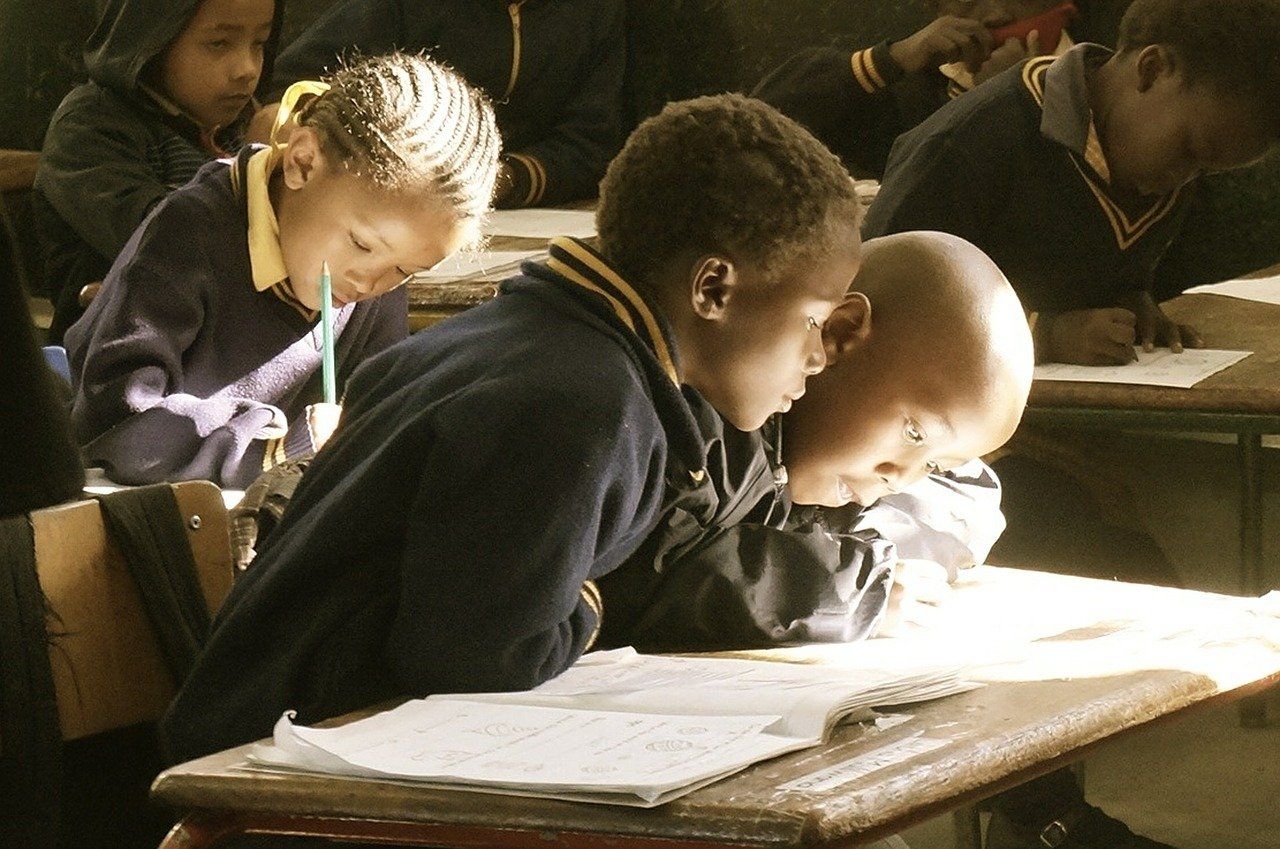

Think back for a second to your childhood days at school. It’s not hard to guess that a number of those memories are about the lighter moments - the invented and reinvented games, the stories shared in lunch breaks, and the lighthearted competitions with friends. As children, we treasured playfulness. When such moments were a part of our classrooms, they're indelibly imprinted in our minds.

Learning Braille doesn’t have to be any different. While traditional means of teaching Braille have limited what students and teachers can do in the classroom, there are now a number of ways to make play a part of learning. With Thinkerbell Labs’ own Annie, for example, we make games, interactive lessons, stories and songs the heart of an education in Braille. Helping bring these joys to the classrooms of visually impaired children is a wonderful thing.

1. Making Sense of the World Through Play

An essential part of the learning process is using it to find meaning in students’ experiences of the world. This means being able to locate what they’re learning in their everyday lives - be it at school, home, or playing with their friends. Learning through play is meaningful.

Visually impaired children learn about the world around them in the way that it is described - this includes the way their friends play with them, describing the rules and form of their games in senses of touch, movement, and place (“throw the ball to me, I’m here!”). By bringing this world of play through learners’ senses into their classrooms, children are excited by the possibility of learning about what’s fun to them. With Braille, children also have the means to read and write about these parts of their lives that they hold dear.

On Annie, the learning materials - games, stories, and songs - refer to objects and places that children might encounter everyday. The ball that they catch, the trees they might climb, the open field outside their classroom, the wood of their benches. The shapes on Annie themselves are designed to make associations with their names through the instructions. Annie’s a companion for blind and visually impaired children - what better way to be one than to be a part of their lives’ stories?

2. Bringing Joy to Learning

Too often, when we think of school, we think of bored faces and monotonous afternoons. Bringing play into children’s places of learning can not just help dispel this monotony - it can make learning itself joyful, and by extension, something kids are happier to be an active part of. What if we can make learning Braille what makes children happy, by incorporating what brings them joy in their games into their lessons?

On Annie, we’ve developed several games that help children hone their skills in reading and typing in Braille, as well as better their spelling and vocabulary. But these games are designed to be, first and foremost, fun. Kids play to get quicker at hitting their marks on the Braille cells in Whack a Braille, or get a higher score as they learn to spell out words in Braille in Letter Race. The reward, to us, is more than student performance - it’s also the bright smile on their faces when they get a new high score on Annie.

3. Making Learning Engaging Through Interactivity and Games

Bored kids are also disengaged learners. Education cannot be a one-way street; to keep children interested and active in the classroom, it’s important to move from how lessons can be taught by a teacher, to how children can learn through games and interactive activities. Play can help challenge children's thinking about what they learn, making learning more engaging.

For children with visual impairments, whose sense of the world is a mix of touch and sound, holding their interest depends on applying both to their lessons. Games, and other forms of interactive play, bring these senses together in ways that draw children’s attention and concentration, so they’re fully engaged in the activity. This is evidently great for learning.

Annie’s games are built to challenge and focus children’s speed, accuracy, and knowledge of reading, writing, and typing the Braille script, along with their ability to associate this script with letters and words. Whether they’re playing Whack-a-Key and learning the order of Braille typing keys, or spelling the words that start with the letter they’ve chosen to learn, the focus is on keeping the learners engaged in interacting with Annie. With both the playful affirmations and feedback Annie gives the learner, they’re keen to know Braille better.

4. Practicing, Learning, and Growing

It’s said that practice makes perfect. But with learning through play, practice is the point, not perfection. Children play to practice skills, try out possibilities, revise what they’ve learnt and discover new challenges, leading to deeper learning. When this sort of iterative practice becomes play, children can better their own skills and learning through methods that become natural to them.

The tactile form of Braille, in particular, means that fluently reading, writing, and typing in Braille takes a fair amount of practice. Luckily, this same form - particularly, the dots - makes it easier to gamify learners’ interactions with the script through clickable keys, slates, and styluses. The more kids play these games then, the more the skills they need to read, write, and type in Braille improve.

This is the basis for the interactive lessons and games on Annie, which make it a point to connect each key a learner pressed, each word they read on the Braille cell, and each word they write on the Braille slate to a gamified element. Whether it be through a quick game at the end of a lesson, or a unique game like Braille Pop - that creatively challenges children to think about the connection between the Braille dots and the spelling of a word - Annie nudges the learner to keep getting better at Braille through the games they play.

5. Learning With Each Other

It’s always a lot of fun to play with others. It fosters cooperation and a competitive spirit, encourages children to have fun in communicating with each other, and creates a space for warm bonds to form between peers. And when teachers become participants in learning through play, many of the barriers children put up in treating a teacher as an authority figure begin to fall away. Social interaction is the cornerstone of such learning.

For visually impaired children, a sense of community is key to participating enthusiastically in their classes. When playing with friends, they also discover creative ways to communicate how they want to play the game, what they want from their friends while playing with them - and even develop complex communicational skills like negotiating a compromise (who gets to play with Annie next?). They talk and listen to each other, which is also key to learning from each other. Where necessary, teachers can also be involved in supporting such communication as well as encouraging friendships - they can be guides to the social landscape that the kids are finding their way around.

The Annie Smart Classes, where children take turns to learn from and play with Annie, as well as compete with their friends to make progress on their lessons and get on the games’ leaderboards, are as much a playground as a classroom. And with catchy songs and stories to talk about, we’ve been overjoyed to listen in on children sharing these experiences with their friends outside the classroom too!

Erasing the Differences between Play and Learning

Too often, play-based learning is abandoned in favour of a purely academic environment, even for young children! As we’ve learnt through Annie, this doesn’t need to happen; interactive lessons and games, with friends and teachers, can be an exciting and engaging way for visually impaired children to learn Braille. All it takes is a little bit of creativity, and a rekindling oh childlike joy and curiosity.